Link to Part I

The Role of the US in Central Asia

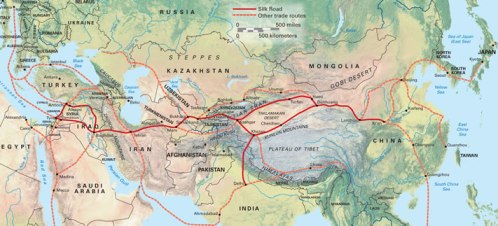

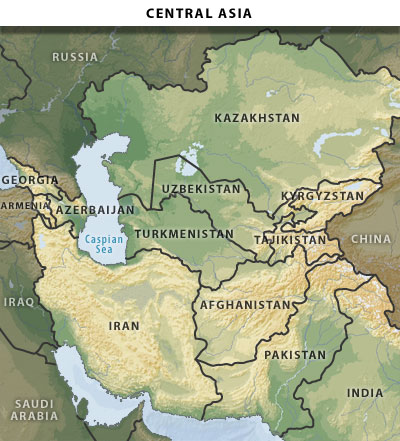

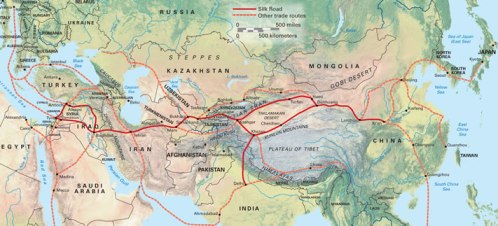

Turkestan, as this region is also known, has been a pivotal region for large states and empires throughout history due to its resources and strategic location. The great Persian Empires (the Achaemenid, Parthian, and Sassanid Empires and subsequent Islamic Caliphates), the Huns, the Mongols, the Hans of China, and a number of Turkic empires as well as many others have all placed great importance on this region despite its distance from the power base of each of these civilizations. A more recent example of the importance of this region is the Great Game or Tournament of Shadows where the Russian and British empires competed for influence over most of the 19th century. One common factor over time has been the importance of Central Asia’s trade routes. It’s the point where the ancient Silk Road exits China towards Arabia, Persia, the Mediterranean, and Europe.

As the ancient Silk Road was an integral part of the development of empires and regional civilizations throughout history, the movement of resources from and through Central Asia is vital to the development of not only these states but other state actors with interests in this region in what is still the post-Cold War era. Central Asia is a platform for economic expansion, resource extraction and transport, and also serves as strategic depth for the activities of large states in the region. The infrastructure, resources, and foreign military activities all have a great effect on the foreign policy of the US, regional powers Russia and China, and the developmental prospects of the Central Asian Republics.

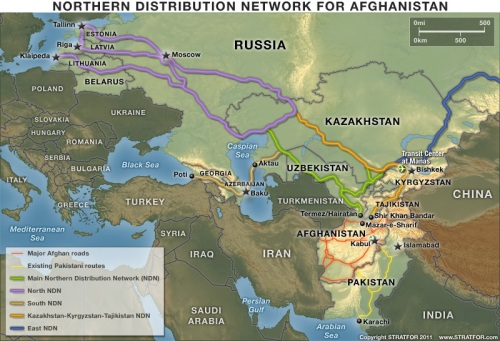

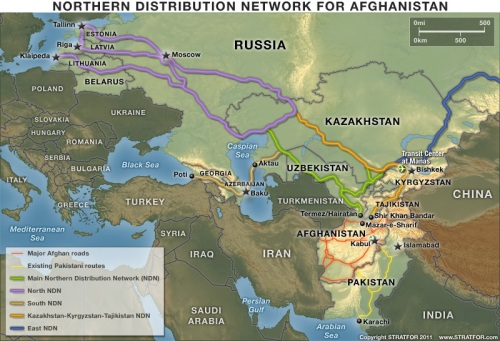

The Northern Distribution Network

The Northern Distribution Network (NDN) is the supply route for NATO and US forces operating in Afghanistan and has been vital since the closing of Karachi as the primary supply chain due to a breakdown in diplomacy between the US-NATO and Pakistan. With attacks on supplies increasing in 2008, the US set about securing an alternative route for supplies shipped into Afghanistan. In April of 2008 the US struck an agreement with Russia to transport non-lethal supplies through its territory to counter the increasing instability of the Karachi route. This agreement was later expanded during a summit in Moscow between then President Medvedev and Barack Obama to include both military and non-lethal supplies (McDermott, 2009).

Click on any picture for a full size view

With Russian permission in place, the US went about securing a series of agreements in Central Asia to complete the supply chain. In early 2009, the US completed agreements with four of the five Central Asian republics in what has to be considered a diplomatic sensation from US Secretary of State Hillary Clinton and the State Department (Krol, 2009; McDermott, 2009; Demytrie, 2009).

By solving one logistical issue, though, the US has potentially created another. In 2010 the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS), a bipartisan ‘think tank’ based in Washington D.C., published a report titled The Northern Distribution Network and Afghanistan which concluded that “By extending U.S. military supply lines across several countries fraught with internal problems, external frictions, and a history of mercurial relations, the United States opens itself to manipulation by geopolitical forces.” (Sanderson and Kuchins 2010, 31). Indeed, the US now finds itself competing with both China and Russia for influence in the region as well as juggling the demands associated with a new found leverage being utilized by the Central Asian republics.

At the time of the CSIS report the US had already been evicted from the Karshi-Khanabad air base in Uzbekistan in 2005 (Wright and Tyson 2005). Uzbek President Islam Karimov seemed determined to explore independence by leaving the Collective Security Treaty Organization and then banning all foreign military bases on its soil, both taking place earlier this year (Abdurasulov 2012; Isachenkov 2012). This report was also written at a time when the President of Kyrgyzstan, at the time Kurmanbek Bakiyev, had appeared to be leveraging the US and Russia over the existence of the US military base at Manas to the tune of tripled rent payments from the US (from $17 million to $60 million) and a pledge of over $2 Billion in future aid from Russia (Kucera Jan 5 2012).

The ulterior goal of the NDN is to eventually become a commercial transit route which is an attempt to develop economic integration in Central Asia in what is referred to as the New Silk Road Initiative (Kucera Oct. 25, 2012). However, there are multiple areas of concern that must be addressed for this to happen. How can a plan for regional economic integration exclude Iran? (Kucera Oct 25, 2011) Will economic benefits be enough for Afghanistan’s neighbors to work together? (Kucera Oct 19, 2011) How will Afghanistan overcome a geography that does not lend itself to becoming the ‘Asian Roundabout’? (Kucera 2010) These questions need answers.

| Kazakhstan: $137.3 million |

| Kyrgyzstan: $218.1 million |

| Tajikistan: $11.7 million |

| Turkmenistan: $820.5 million |

| Uzbekistan: $105.9 million |

Despite the uncertainty there have been positive trends to this economic initiative thus far. The initial returns of the NDN on Central Asian economies were less than what was hoped for and this is likely one explanation as to why Uzbekistan has been less than eager to cooperate, not to mention their World Bank ranking of 154th on “ease of doing business” (Kucera Oct 26 2012). The latest numbers of US spending in Central Asia as reported from the Defense Logistics Agency (See table) are much more reassuring that the initiative could have some momentum.

The eye-popping number of $820 million to Turkmenistan is due to the massive amounts of fuel it supplies to the US and the low number of $11 million to Tajikistan is due to the lack of supply points for the NDN in that country as well as numerous concerns that the US has about Tajik human rights and democracy (Kucera Dec 3, 2012; Nichol Aug 31 2012).

There are other developments that warrant attention with regards to the objectives of the US role in Central Asia. In his State of the Union address on January 5, 2012, President Barack Obama identified his plan to strengthen the US presence in the Asia-Pacific region, to ‘pivot’ US resources to the region. The underlying notion is that national security, foreign policy, and economic interests will be focused on Asia. China’s reaction was that the US plan was to limit Chinese economic expansion in the area and voiced its disapproval. If containment of China is a goal of the US shift in regional emphasis then the development of economic infrastructure in Central Asia is very likely a hedge against Chinese economic expansion.

Another potential development of US activities in Central Asia is the counter-balance of the strategic depth of Russia’s ‘soft underbelly’. The perceived US role in the Caucasus’ and Central Asia’s “Color Revolutions” in the late and mid-2000’s has generated a somewhat skeptical attitude towards the US and more recent competition with Russia over military bases in Uzbekistan and Kyrgyzstan highlight this thinking. (Kucera Dec 4, 2012) Particularly, the situation regarding the US transit center at Manas highlights this issue as Kyrgyzstan is the only country in the world to host both US and Russian military facilities. The willingness of the Bakiyev regime to play Washington and Moscow against each other offered a glimpse of the type of competition that could take place in the future.

The Role of Russia in Central Asia

Russia has considered Central Asia to be within its sphere of influence since these republics gained their independence from the Soviet Union two decades ago and they hold both strategic and economic importance for Russia today. Kazakhstan in particular is the home of several facilities for Russian defense and industrial production as well as being the second largest oil producing country of the former Soviet Union. Turkmenistan is a petrol state with huge amounts of natural gas that it exports to both Russia and China at a rate that is much higher than the rest of the Central Asian republics. Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan feature five Russian military facilities between them and recently signed a massive arms deal that is thought to counter US influence in Uzbekistan, which is distancing itself from Russia. (Chernenko, Karabekov, and Belyanina 2012) In what has been referred to as Russia’s ‘soft underbelly’ these states provide strategic depth for its southern region as well as an abundance of resources vital to the Russian economy.

The Curiosity of Manas

Since military operations began in Afghanistan in 2001 the US has had varying degrees of influence in Central Asia and at times has directly confronted Russian interests. No other country highlights this as well as Kyrgyzstan, which has the distinction of being the only country in the world with both Russian and US military facilities. When faced with the prospect of the military base at Manas being closed due to a leveraging of Russian aid in 2009, the US agreed to triple its rent payments and rename the facility a ‘transit center’ for non-lethal goods. When Kyrgyz President Almazbek Atambayev was elected in 2011 he appeared to be more pro-Russia and not as open to monetary incentives as the Bakiyev regime and quickly followed suit by announcing the closing of the US transit center at Manas in 2014 when operations in Afghanistan are scheduled to draw-down. (Kucera Jan 5, 2012)

Considering the role the US is suspected to have played in 2005’s Tulip Revolution, the questionable election of then President Kurmanbek Bakiyev, and in turn the suspected Russian role in his regime being overthrown, state competition for political influence in Kyrgyzstan has appeared to have gone public. (Spencer 2005; Makhovsky 2010) Subsequent events in Central Asia appear to support this line of thinking: a bilateral trading agreement in 2011 between the US and Kazakhstan, Russia’s biggest resource and defense partner in the region, and the notion of Uzbekistan allowing a US military base after the military withdrawal in 2014 both point towards ongoing regional competition between the two states. (United States Trade Representative 2012; Solovyov 2012)

If there is an ongoing competition between the US and Russia in Central Asia, why let the US transport goods through Russian territory using the NDN? Russia and the US both have a vested interest in Afghan security and it was Russia in fact that suggested the US use Russian land and airspace to transport its goods likely due to the increased leverage it offered to counter the ongoing expansion of the NATO missile shield in Eastern Europe. (Kucera Nov 28, 2011) Russia is also going through a demographic crisis and gender age gap that is directly related to it being one of the countries most affected by Afghan opium production. (Heineman 2011; Lally 2010)

Gazprom in Central Asia

The resources of Central Asia and Russian interests are closely tied to the state controlled Russian energy company Gazprom. It is the largest extractor of natural gas in the world and is the primary reason that Russia is ranked 2nd in oil production and oil exports as well as 3rd in natural gas production and exports in 2011. (CIA Factbook) Gazprom features agreements with all five Central Asian republics and the regions natural gas exports account for around 7% of its gas production. Natural gas represents around 60% of the company’s total sales. (Factbook: Gazprom in figures 2007-2011)

In 2009, Central Asian exports accounted for as much as 13% of Gazprom’s total natural gas production but US, European, and Chinese interests sought to break the Russian company’s monopoly in the region. (Gazprom factbook 2011; Lillis 2008) In order to retain gas imports, Gazprom agreed to pay European price levels which affected the profitability of the region and saw the company accordingly cut its production and production costs. (Eurasianet.org 2009) Recently in 2012 GazpromExport, the trading arm of Gazprom, called for a forecast of Central Asian/Caucasian exports and consumption until 2025. These states were increasing their association with China and Gazprom needed a more accurate picture of its standing in the region, according to the announcement. (Blagov 2012) The companies influence and monopoly in the region has diminished and this has affected profits. One way in which Russia is attempting to counter this is through the Eurasian Economic Union as well as a customs union in Central Asia.

Russian influence appears to be either waxing or waning in Central Asia depending on the country and situation. It has increased its military presence in the south with $1.3 billion in arms deals with Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan and extended the lease of its military facilities in Tajikistan by 30 years. It also has created a Eurasian Customs Union to better integrate and facilitate trade with its Central Asian partners. On the other hand, its Central Asian energy profits through Gazprom have decreased, it saw its largest natural gas importer sign a new agreement with China, and it was denied a military base in Uzbekistan, who not only rejects the idea of joining the customs union but also recently decided to leave the Russia-led Collective Security Treaty Organization (CSTO). Russian motivations in the region appear to be juxtaposed to the activities of China and the US in some areas while in cooperation in others. This current presence of Russia in Central Asia lends itself to uneasy alliances that, at times, will see the more powerful actors that concern themselves with this region engaged in state competition for its resources, be they energy, infrastructure, or military.

The Role of China in Central Asia

China is Central Asia’s largest trading partner with a total trade value of almost $17 billion in 2011 as well as the largest current investor in Afghanistan. (Saipov 2012) According to the CIA Factbook, China is the largest trading partner for imports, exports, or both in every Central Asian republic with the exception of Uzbekistan where it ranks 3rd in each. In addition to the large amount of trade with Central Asia, China has invested in huge infrastructure projects in the region that also acts as strategic depth against potential threats to it resource production center in the western Xinjiang province.

China’s New Silk Road

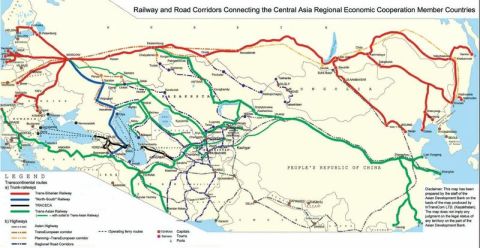

As the ancient Silk Road was an integral part of the development of empires and regional civilizations throughout history, the movement of resources from and through Central Asia is vital to the development of these states and no country has contributed more to this region’s infrastructure and economic development than China. As mentioned before, just the trade between Central Asia and China totaled almost $17 billion last year and this does not include the cost of infrastructure projects completed or ongoing.

The Ancient Silk Road from silkroadproject.org

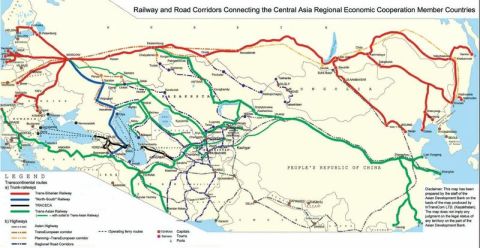

In a return of history, the modern infrastructure developments in Central Asia closely resemble the Silk Road paths of antiquity.

In the graphic shown above nearly all of the Asian rail systems (green) and highways (blue dotted lines) were built or contributed to by China.

While there have been too many projects over the last decade to list, the ongoing works of Chinese industry in Central Asia include: a $2 billion railway from China’s Xinjiang province through Kyrgyzstan and to Uzbekistan, thirty agreements totaling $5.3 billion with Uzbekistan in infrastructure and financial investments, and a $80 million road and tunnel project in Tajikistan (Rotar 2012; Saipov 2012; Vinson 2012). Talk of China and a ‘New Silk Road’ has been ongoing for at least the last few years (Eimer 2010; Rickleton 2011).

While China has invested billions in Central Asia, its focus in the region is believed to be on securing a corridor to Afghanistan and its many resources (Saipov 2012). China received the largest investment project to date in Afghanistan with a $3.4 billion contract to extract copper at a mine near Aymak and there is also $300 million to be invested in three oil fields in Northern Afghanistan that will likely be exported via the Pakistani port at Gwadar, which was recently handed over to the control of China (Wines 2009; Times of India 2012; Yu 2012).

The role of China in Central Asia is less complex than those of the U.S. and Russia and because of that its motives are more easily ascertained. Its thousands of miles of shared borders with its Central Asian neighbors seem to be less of a concern due to a naturally mountainous western perimeter and any threats of Islamic extremism from the region are less of a concern than its own growing extremist problem in the autonomous Xinjiang province. China mainly concerns itself with the extraction and transport of resources to and from both the Xinjiang province in the west and the Gwadar port in Pakistan to fuel its growing energy needs and trade demands. It utilizes vast amounts of capital for investment in Central Asian infrastructure, energy extraction and trade agreements that are mutually beneficial in both short- and long-term for all parties involved. The acquisition of resources is necessary in order to develop its large middle class and ongoing western expansion.This is particularly true since China is the largest consumer of energy in the world since 2010. Former National Security Advisor Zbigniew Brzezinski noted in his book The Grand Chessboard, “A “Greater China” may be emerging, whatever the desires and calculations of its neighbors, and any effort to prevent that from happening could entail an intensifying conflict with China.” (1998)

Conclusion

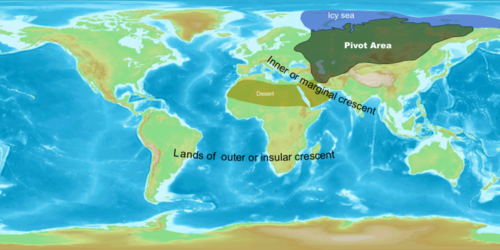

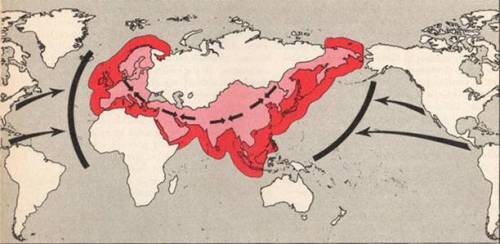

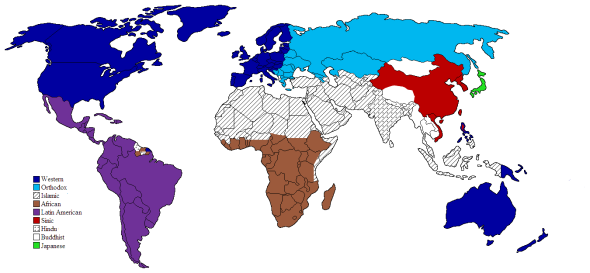

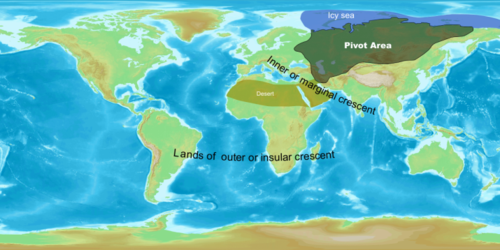

To answer the question ‘Do geopolitical theories help explain U.S. foreign policy decisions concerning Central Asia?’ first we must consider the evolution of the geopolitical works already examined. Halford Mackinder’s Heartland Theory identified Central Asia as the ‘pivot’ of the world’s politics, the axial portion of the Eurasian continent that possesses most of the world’s population and natural resources. Mackinder noted that if any civilization should control the Eurasian continent, then that state could claim dominion over the entire world. It is Mackinder’s identification of this strategically important region that is the distinguishing feature of his work today. Writing for the U.S. Army War College journal Parameters, Professor Christopher Fettweis confirmed in 2000 that, “Eurasia, the “World Island” to Mackinder, is still central to American foreign policy and will likely to continue to be so for some time. Conventional wisdom holds that only a power dominating the resources of Eurasia would have the potential to threaten the interests of the United States.” (Fettweis 2000, 58)

Nicholas J. Spykman’s The Geography of the Peace re-evaluated Mackinder’s regions and identified the Inner Crescent as the Rimland which is also the area he identified as “Eurasian Conflict Zones” where containment of the USSR would see opposing forces clash. At this time Central Asia was part of the USSR and today it could be considered part of the Rimland or Eurasian Conflict Zones. Distinguishing this region from the pivot area helps explain the modern idea that containment of China is indeed a strategy within the ‘Conflict Zone’ and makes sense due to the changes of the political map since the 1940’s, when Spykman formulates his ideas. (Pilko 2012; Hayden 2012)

This reorganization does not necessarily compromise the idea of Central Asia as The Heartland, according to Spykman. He notes, in 1942, that the natural obstacles of transportation will limit the power potential for the region for the immediate future. Today we see Central Asia encompassing characteristics of both Heartland and Rimland as well as realizing a growing influence on its powerful neighbors and the development of infrastructure (railways, highways, and pipelines) to export their massive resources is the lynchpin to their independence from foreign influence.

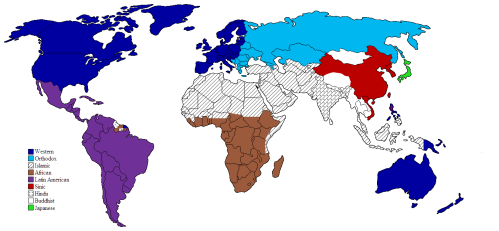

The evolution of these geopolitical models that account for Central Asia’s move from Pivot to Conflict Zone is utilized by Samuel P. Huntington in The Clash of Civilizations? The fault lines of civilizations that Huntington cites as the areas of future conflict in the post-Cold War era neatly fall within the Eurasian Conflict Zones with Central Asia the northern border of Islamic culture. More importantly, Huntington’s Clash identifies that “At the macro-level, states from different civilizations compete for relative military and economic power, struggle over the control of international institutions and third parties, and competitively promote their particular political and religious values.” Competing Silk Road economic corridors, leveraged rent for military bases, large arms deals, resource extraction, and huge infrastructure projects highlight the competition of just the past few years in Central Asia between the region’s most powerful actors. A clash of civilizations, as defined by Huntington, seems to indeed be taking place.

The U.S. is currently engaged in direct competition with both Russia and China for Central Asian influence. Kyrgyz military facility disputes, Turkmen gas sales, Uzbek basing rights, and Kazakh trade agreements are just some friction points of the regional competition taking place between the U.S. and Russia. Given the broader context of the conflict in Syria and Russian displeasure with Afghan opium production as well as U.S. missile placement in East Europe this adversarial stance between the two is poised to become even more public. In a December 6th article released by the Associated Press, Hillary Clinton warned against the path that Russia seemed headed towards and with regards to Central Asia specifically stated:

“There is a move to re-Sovietize the region,” Clinton lamented. “It’s not going to be called that. It’s going to be called customs union, it will be called Eurasian Union and all of that,” she said, referring to Russian-led efforts for greater regional integration. “But let’s make no mistake about it. We know what the goal is and we are trying to figure out effective ways to slow down or prevent it.” (2012)

That the U.S. is directly involved with every Central Asian country through the NDN and has been attempting to counter Russian influence as highlighted in Kyrgyzstan over the past few years, is an example of the type of competition that should be expected in the future.

The U.S. stance towards China experienced a paradigm shift when President Obama announced a “Strategic Pivot” towards the Asia-Pacific region last January. The move was widely believed to be a Chinese containment strategy and the subsequent visits by President Obama and members of his cabinet to sensitive areas of U.S.-China relations highlight this thinking. (Eckert 2012) While the Asia-Pacific pivot has begun over the past year, activities in Central Asian have been potentially ongoing since the suspected involvement of the U.S. in the color revolutions in the mid 2000’s and at least since the NDN was created in 2009. In 1998, former National Security Advisor Zbigniew Brzezinski proclaimed in his book, The Grand Chessboard that, “without an American-Chinese strategic accommodation as the eastern anchor of America’s involvement in Eurasia, America will not have a geostrategy for mainland Asia; and without a geostrategy for mainland Asia, America will not have a geostrategy for Eurasia.” The U.S. now has a presence in both Eastern and Central Asia. The Central Asian infrastructure that China has been so instrumental in developing has been referred to as a New Silk Road since 2006. With the announcement of the plans to turn the NDN into an economic corridor after the military drawdown in 2014, any notion that the U.S. isn’t attempting to counter China’s growth should vanish.

What do geopolitical theories tell us to expect from the future of US foreign policy in Central Asia after the withdrawal of military forces from Afghanistan in 2014? When considered with the analysis of current events above, an increase in state competition for influence and resources in Central Asia should be expected. The situation will not resemble a ‘triumvirate’ of competing powers for the ability to rule. A new level of triangular diplomacy will be featured between the U.S., Russia, and China concerning this region’s economic integration and its development.

The U.S. cannot afford to lose a foothold in Central Asia and will seek to obtain military basing rights in one of these republics, Uzbekistan being the suspected choice. This is even more important considering that any forces in Afghanistan after 2014 will be precluded from conducting foreign military operations. The development of the NDN into an economic corridor is paramount if the U.S. wishes to see its influence grow in the region. The apparent issue is that China seems much better equipped to develop long-lasting economic relationships and already has a much stronger foundation in Central Asian economies. With regards to Russia, the U.S. will seek trade agreements to balance the NDN corridor and to help deter the Central Asian republics from joining a Eurasian customs union that would otherwise achieve the same result of increased economic performance. Increased cooperation with willing Central Asian partners will foster long-lasting engagement in the region but at the expense of either Russia or China, or both.

References

Abdurasulov, Abdujalil. 2012. “Uzbekistan, key to Afghan war drawdown, to ban foreign military bases.” Christian Science Monitor, 30 August.

Belyanina, Cyril, Elena Chernenko and Kabai Karabekov. 2012. “Central Asia divided on the basis of basic.” Kommersant, 23 August.

Brzezinski, Zbigniew. 1998. The Grand Chessboard: American Primacy and Its Geostrategic Imperatives. New York: Basic Books

Blagov, Sergei. 2012. “Russia Eyes New Far Eastern Gas Export Hub, Reassesses Central Asia.” Jamestown Foundation, 21 November.

Demytrie, Rayhan. 2009. “Tajikistan agrees US supply route.” BBC News, 21 April

Eimer, David. 2010. “China builds a ‘new Silk Road’ to pave over its troubles.” Telegraph, 7 November.

Fettweis, Christopher. 2000. “Sir Halford Mackinder, Geopolitics, and Policymaking in the 21st Century.” Parameters Summer ed.: 58-71.

Heineman Jr. Ben. 2011. “In Russia, a Demographic Crisis and Worries for Nation’s Future.” Atlantic, 11 October.

Huntington, Samuel P. 1993. “The Clash of Civilizations?” Foreign Affairs, Summer Ed.

Isachenkov, Vladimir. 2012. “Uzbekistan quits Russia-dominated security pact.” Associated Press, 28 June

Krol, George A. 2009. Approaching the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe Chairmanship: Kazakhstan 2010. U.S. Diplomatic Mission to Kazakhstan.

Kucera, Joshua. 2012. “Central Asia: Washington Must Adapt to Diminished Role in Central Asia – Expert” EurasiaNet.org, 4 December.

——, ed. 2012. “Turkmenistan Big Beneficiary Of Pentagon Money, While Uzbekistan Lags” EurasiaNet.org, 3 December.

——, ed. 2012. “U.S. General Says NDN Will Lead To New Silk Road” EurasiaNet.org, 1 December.

——, ed. 2012. “Central Asia: NDN Not the Cash Cow Local Leaders Expected” EurasiaNet.org, 26 October.

——, ed. 2012. “NDN And The New Silk Road, Together Again” EurasiaNet.org, 25 October.

——, ed. 2012. “”Bakiyev Can Be Bought”: U.S. Embassy Tied Rent for Kyrgyz Air Base To President’s Reelection” EurasiaNet.org, 5 January.

——, ed. 2011. “Russia Threatens To Cut Off NATO Afghanistan Transit” EurasiaNet.org, 28 November.

——, ed. 2011. “Central Asia: Iran Left Out of New Silk Road Plans” EurasiaNet.org, 22 November.

——, ed. 2011. “Can Afghanistan’s Neighbors Keep It From Falling Apart?” EurasiaNet.org, 19 October.

——, ed. 2010. “Gen. Petraeus, the Northern Distribution Network and the “modern Silk Road”” EurasiaNet.org, 2 July.

Kuchins, Andrew C. and Thomas M. Sanderson. 2010. “The Northern Distribution Network

and Afghanistan.” Center for Strategic and International Studies: p. 31.

Lally, Kathy. 2010. “Russia’s heroin problem and ongoing battles over Afghan poppy fields.” Washington Post, 30 October.

Lillis, Joanna. 2008. “Russia Makes Financial Gamble to Retain Control of Central Asian Energy Exports.” EurasiaNet.org, 13 March.

Mackinder, Halford. [1904] 2004. The Geographical Pivot of History. The Geographical Journal 170 (December): 298-321.

Makhovsky, Andrei. 2010. “Bakiyev says Russian anger a factor in Kyrgyz revolt.” Reuters, 23 April.

McDermott, Roger. 2009. “Uzbekistan Signs Transit Route Agreement” Jamestown Foundation, 7 April.

——, ed. 2009. “Medvedev Expands the Northern Supply Route to Afghanistan” Jamestown Foundation, 7 July.

Nichol, Jim. 2012. “Tajikistan: Recent Developments and U.S. Interests.” Congressional Research Service, 31 August: p. 6-8.

Office of the United States Trade Representative. 2011. United States and Kazakhstan Sign Bilateral Agreement that will Open Markets, Support American Jobs. Washington, D.C.

Rickleton, Chris. 2012. “Kyrgyzstan: China Seeks “Silk Road” on Rails.” EurasiaNet.org, 3 November.

Rotar, Igor. 2012. “Chinese ‘Expansion’ in Kyrgyzstan: Myth or Reality?” Jamestown Foundation, 7 November.

Saipov, Zabikhulla. 2012. “China’s Economic Strategies for Uzbekistan and Central Asia: Building Roads to Afghan Strategic Resources and Beyond” Jamestown Foundation, 21 September.

——, ed. 2012. “China deepens Central Asia role.” Asia Times Online, 25 September.

Solovyov, Dmitry. 2012. “Uzbekistan bans foreign military bases on its land.” Reuters, 2 August.

Spencer, Richard. 2005. “Quiet American behind tulip revolution.” Telegraph, 2 April.

Spykman, Nicholas J. 1944. The Geography of the Peace. New York: Harcourt, Brace & World

Times of India. 2012. “China confirms takeover of Pak’s Gwadar port.” 4 September.

Tynan, Deirdre. 2010. “Kyrgyzstan: Manas Fuel Contractors Have Fuzzy Ties with Local Firms.” EurasiaNet.org, 1 December.

Tyson, Ann Scott and Robin Wright. “U.S. Evicted From Air Base In Uzbekistan” Washington Post, 30 July.

Vinson, Mark. 2012. “Tajikistan’s new roads boost civil, military links.” Asia Times Online, 10 November.

Wines, Michael. 2012. “China Willing to Spend Big on Afghan Commerce.” New York Times, 29 December.

Zabortseva, Yelena Nikolayevna. 2012. “From the “forgotten region” to the “great game” region: On the development of geopolitics in Central Asia” Journal of Eurasian Studies 3 (2012) 168-176.